The Kurdistan Liberation Movement and its people were continuously searching for an opportunity to liberate themselves from the oppression, tyranny, and crimes of the Ba’ath regime. The Kurds, along with Kurdish political parties and Peshmerga forces, over many years, faced several political activities, uprisings, face-to-face wars, and various revolts against the dictatorial Ba’ath system, encountering ruthless killings and suppression but never yielding. The rebellion of 1991 had many precursors; the Kurdish nation, after facing several genocides in the 1980s and continuous massacres under total suppression, was living in dire conditions. Thus, the onset of the Gulf War due to Iraq’s invasion of Kuwait for various pretexts and the swift international reaction, including the issuance of several international resolutions against Iraq, economic sanctions, and the defeat of its forces in the war, provoked significant responses in the region. This situation led the Kurds and the Shiites of Iraq to think that an appropriate opportunity had arrived to get rid of Saddam and the Ba’ath regime. Even the statements of American officials and coalition forces, especially George H.W. Bush, the President of the United States, encouraged the people of Iraq in general to overthrow the Ba’ath regime, which was one of the reasons for this uprising. Bush, in several speeches on Voice of America on February 15, 1991, March 1, 1991, and on Radio Free Iraq on February 24, 1991, urged the Iraqi people to rise and overthrow Saddam. Moreover, the opposition parties in the south, Kurdish parties, Peshmerga, and the Kurdish people believed that after the defeat of its forces, the Ba’ath regime had weakened, and this time, the United States would support them.

The invasion of Kuwait by Iraq and the First Gulf War.

The Ba’ath regime of Iraq continued their past crimes and hostilities, leading to a new aggression, the invasion of Kuwait in August 1990, initiating the war between Iraq and Kuwait and its occupation under the pretext of Iraq’s debts to Kuwait, which Kuwait was not willing to forgive. The aim of this invasion was the annexation of Kuwait as Iraq’s 19th province. The occupation of Kuwait by Iraq was completed within 13 hours and was immediately met with international condemnation. United Nations Security Council Resolution 660 was issued, followed unanimously by Resolution 661, imposing economic sanctions against Iraq. Furthermore, with the adoption of United Nations Security Council Resolution 678 on November 29, 1990, Iraq was given a final opportunity until January 15, 1991, to implement Resolution 660 and withdraw from Kuwait. After the deadline expired, states were authorised to use “all necessary means” to compel Iraq to withdraw from Kuwait. Initial efforts to drive the Iraqis out of Kuwait with aerial and naval bombardments started on January 17, 1991, marking the beginning of the Gulf War, which lasted five weeks and resulted in the defeat of the Iraqi forces by a coalition of 42 countries led by the United States, involving 700,000 troops in Operation Desert Storm. Iraq was driven out with significant losses, especially during its retreat from Kuwait, marking a major defeat. This provided a new opportunity for uprisings against the people of Iraq in general across various regions of Iraq.

Uprising 1991

In southern Iraq, on March 1, 1991, one day after the ceasefire of the Gulf War, an uprising in Basra began against the Iraqi government. This uprising spread within a few days to all the major Shiite cities in southern Iraq: Najaf, Amara, Diwaniyah, Hilla, Karbala, Kut, Nasiriyah, and Samawah.

On March 5, 1991, the uprising, with the cooperation of Peshmerga forces of the Kurdish coalition, which consisted of all Kurdish parties and Kurdish popular forces, started in the city of Rania and, in the following days, spread to the Bazian one and two regions, the plains of Betwata and Pshdar, Sulaymaniyah, Chamchamal, Halabja, Arbat, Zharine, Samud, Nazdur and Barika, Piramagroon, Koysanjaq, Shaqlawa, Kifri, Khoramatu, Miseef, Taq Taq, Rowanduz, Qaradagh and Agjalar, Harir and Batas, Khalifan, Sipeil and Suran, Choman and Haji Omran and Mergasur, Erbil, Jalawla, Makhmur, Aqrah, Khanaqin, and Sheikhan, Zakho, Pirda, Jabara, Kalajo, Duhok, and within 16 days managed to advance to Kirkuk and take control of all cities. Contrary to the south, where slogans were mostly religious and Shi’a-oriented, the Kurdish uprising was accompanied by political slogans, including democracy for Iraq, autonomy for Kurdistan, and independence and freedom for the nation.

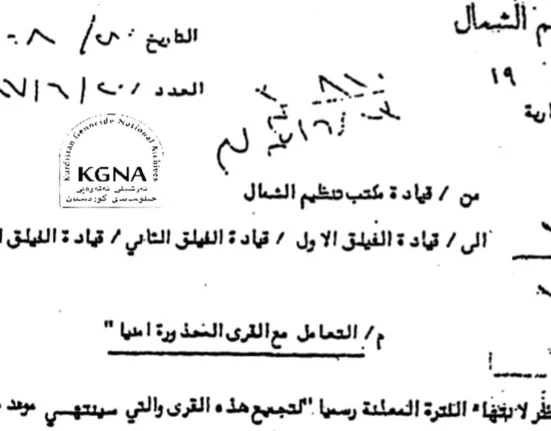

The people involved in the uprisings in all cities, both in the south and in Kurdistan, attacked the Ba’ath security institutions that had been centres of torture and slaughter for many years, including the security administration in Sulaymaniyah, known as “Amn-e Suraka,” which was one of the most dreaded prisons. As a result, all prisoners were freed, and a large amount of government documents related to the Anfal genocide and chemical attacks on people, including Kurds and Shiites, were obtained. The Ba’ath regime had systematically tortured and massacred hundreds of thousands of Kurds, Iraqis, and other ethnic communities in various ways over the years, totalling 14 tons of documents that were later transferred to the United States.

The uprising was successful; Saddam Hussein requested negotiations from the heads of parties, but they refused. While initially, the United States and its allies had called for an uprising against the Iraqi government and the overthrow of Saddam and the Ba’ath regime across Iraq, they withdrew their support for the rebellion due to the Shiite uprising’s orientation towards the Islamic Republic of Iran and their terrible experience with the rise of Shiite clerics in the 1979 Iranian revolution. Contrary to their previous statements for overthrow, they allowed Iraq to suppress and slaughter the Shiites of the south and the Kurdish uprising again, effectively giving a green light. Tens of thousands of people were arrested and disappeared in the cities, many of whom are still unaccounted for. Millions were forced to migrate and flee from the Ba’athists, with thousands dying from hunger, cold, and the distance travelled.

Despite the Safwan Agreement at the Iraq-Kuwait border, which stated that Iraq should not use air forces and only helicopters were provided due to potential damage to civilian infrastructures, these helicopters were later used by the Iraqi army to fight the uprising and massacre the people. It is noteworthy that during this period, the Iranian group (the People’s Mujahedin of Iran) played a significant role in helping to suppress the Ba’ath regime. They brutally responded to the uprisings of Kurds and Shiites in the mountains, Turkey, and Kurdish-populated areas of Iran. On April 5, the Iraqi government announced the “complete eradication of seditious acts, destruction, and chaos in all cities of Iraq.”

Consequences – Massacres, and Forced Migration

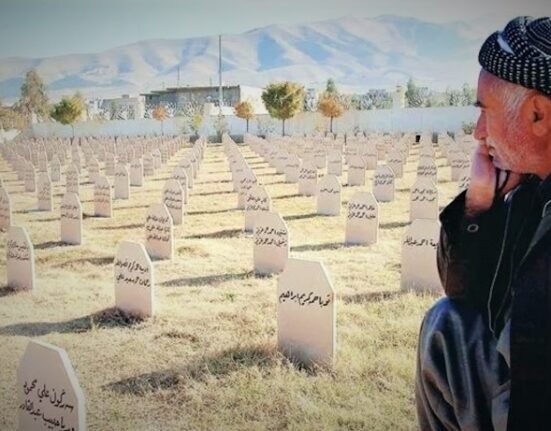

In late March and early April, nearly two million Iraqis, of whom 1.5 million were Kurds, fled from cities and villages to the mountains along the border and into Turkey and Iran, while Shiites in the south fled to the Syrian border or the southern marshes. By April 6, the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) estimated that about 750,000 Iraqi Kurds had fled to Iran and 280,000 to Turkey, with another 300,000 gathered at the Turkish border. The migration was sudden and chaotic, with thousands of desperate refugees fleeing on foot, donkeys, or open trucks and tractors. Many were killed by Iraqi Presidential Guard helicopters, which fired on fleeing civilians in several incidents in the north and south. A significant number of refugees were also killed or maimed by landmines laid by Iraqi forces near the eastern borders during the war with Iran. According to reports from the United States Department of State and international relief organisations, between 500 and 1,000 Kurds were killed daily along the Turkey-Iraq border. Some reports indicate that hundreds of refugees also lost their lives en route to Iran daily. It is estimated that between 50,000 to 100,000 people were killed, disappeared, or died from cold and hunger during the uprising. Many of the dead were buried in mass graves.

On April 5, the same day the Iraqi government announced the “complete crushing of seditions, sabotage, and chaos in all cities of Iraq,” the United Nations Security Council passed Resolution 688, condemning the Iraqi government’s oppression of the Kurds and demanding that Iraq respect the human rights of its citizens. From the beginning of March 1991, the United States and some Gulf War allies, by establishing a no-fly zone over northern Iraq, north of the 36th parallel, prevented Saddam’s forces from conducting jet aircraft attacks and provided humanitarian aid to the Kurds. On April 17, United States forces began taking control of areas more than 60 miles inside Iraq to establish camps for Kurdish refugees. The last American soldiers left northern Iraq on July 15. During the Turkish border incident in April, British and Turkish forces clashed over the treatment of Kurdish refugees in Turkey. Many Shiite refugees fled to Syria, with thousands settling in the town of Sayyida Zainab.

In Kurdistan, the conflict continued until October, when an agreement was reached for Iraq to withdraw from parts of the Kurdish region of Iraq. This led to the establishment of the Kurdistan Regional Government and the creation of autonomy for the Kurds in three northern provinces of Iraq—meanwhile, the Iraqi government sanctioned food, fuel, and other goods to the region.

Retaliation in the South

In Southeastern Iraq, thousands of civilians, army deserters, and insurgents began seeking safe refuge in the remote marshlands of the Hawizeh Marsh on the Iranian border. Following the uprising, the Marsh Arabs became notable for collective acts of revenge, along with the disastrous ecological drainage of Iraq’s marshlands and the widespread and systematic forced relocation of the local population. On July 10, 1991, the United Nations announced its intention to open a humanitarian centre in the Hor al-Hammar marshlands to care for those hidden in the southern marshes. Still, Iraqi forces did not allow UN relief teams to enter the marshes or let people out. A widespread government offensive against the refugees, estimated to include 10,000 fighters and 200,000 displaced persons hidden in the marshes, began in March to April 1992 using fixed-wing aircraft. A US State Department report claimed that Iraq had dumped toxic chemicals into the waters to drive out the opposition. In July 1992, the government began efforts to drain the marshlands and ordered the evacuation of the townspeople, after which the army set their homes on fire to prevent their return. A curfew was also imposed across the south, and Ba’ath regime forces began arresting, executing, and transferring a large number of Iraqis to forced camps in the central part of the country.

The Stance of the International Community

At a special session of the United Nations Security Council on August 11, 1992, Britain, France, and the United States they have accused Iraq of conducting a “systematic military operation” against the marshes, warning that Baghdad could face potential consequences. On August 22, 1992, President Bush announced that the United States and its allies had established a second no-fly zone for any Iraqi aircraft south of the 32nd parallel to protect the opposition against government attacks, as authorised by United Nations Security Council Resolution 688.

In March 1993, UN investigations reported the execution of hundreds of Iraqis from the marshes in the preceding months, emphasising that the behaviour of the Iraqi army in the south was “the most worrying development [in Iraq] over the past year.” It was noted that following the establishment of the no-fly zone, the army resorted to long-range artillery attacks followed by ground assaults leading to “heavy casualties” and widespread property destruction, along with claims of mass executions. In November 1993, Iran reported that due to the marshes’ drainage, the Marsh Arabs could no longer fish or cultivate rice, and more than 60,000 people had fled to Iran since 1991. Iranian officials requested global assistance for the refugees. That same month, the UN reported that 40% of the southern marshes had dried up.

In contrast, unconfirmed reports circulated about the Iraqi army’s use of poison gas against villages near the Iranian border. In December 1993, the United States Department of State accused Iraq of “indiscriminate military operations in the south, including burning villages and forcibly relocating civilians.” On February 23, 1994, Iraq diverted the waters of the Tigris River to areas in the south and east of the central marshes, causing floods up to 10 feet deep to render the agricultural land there useless and drive out insurgents hiding there for refuge in the marshes being drained. In March 1994, a team of British scientists estimated that 57% of the marshes had been drained and that the entire marshland ecosystem in southern Iraq would disappear within 10 to 20 years. In April 1994, United States officials stated that Iraq continued its military operations in the remote marshlands of Iraq.